As someone who has three kids in college, articles like the one below are quick to catch my attention. It is a very interesting piece from the Wall Street Journal about how affluent students subsidize less affluent students, even at state schools. It is quite an interesting read, and I think you will find it informative.

Jon Houk, CFP®

More Students Subsidize Classmates’ Tuition

By: Douglas Belkin

Well-off students at private schools have long subsidized poorer classmates. But as states grapple with the rising cost of higher education, middle-income students at public colleges in a dozen states now pay a growing share of their tuition to aid those lower on the economic ladder.

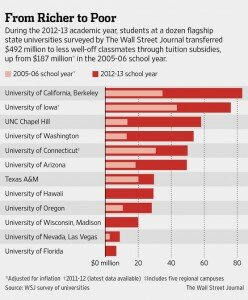

The student subsidies, which are distributed based on need, don’t show up on most tuition bills. But in eight years they have climbed 174% in real dollars at a dozen flagship state universities surveyed by The Wall Street Journal.

During the 2012-13 academic year, students at these schools transferred $512,401,435 to less well-off classmates, up from $186,960,962, in inflation-adjusted figures, in the 2005-06 school year.

At private schools without large endowments, more than half of the tuition may be set aside for financial-aid scholarships. At public schools, set-asides range between 5% and 40% according to the Journal’s survey.

The growth of subsidies is directly related to cutbacks in state aid, according to school administrators. Reductions in public spending for higher education have prompted universities to raise tuition levels, they said, making it tougher for students from poorer families to cover costs. To offset that burden, wealthy and middle-class students pay more in subsidies known as tuition set-asides.

“Without it, there is no way I’d be here,” said Maria Giannopoulos, a 20-year-old junior at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who receives $5,000 a year through the program.

But former classmate Allie Gardner, whose father works at Costco and whose mother is a waitress, said she resented kicking in the extra money.

“It’s this sneaky little thing they’ve put in place because they know we’ll pay it, we’re already taking out loans,” said Ms. Gardner, who graduated in December.

Most public and private universities pool their financial aid from a variety of sources, including endowments, taxes and state scholarship funds. Additionally, public universities have a host of formal and informal subsidies: humanities students subsidize science students, for example, and out-of-state students subsidize in-state students.

The subsidies are taken by public schools nationwide, but there are no figures on the total and very few by campus. The lack of transparency inside university balance sheets makes it difficult to calculate how much one student is subsidizing another. But at least 13 state universities now list the full amount students pay in tuition set-asides.

At the University of Washington for instance, a full-time student paying in-state tuition last year contributed about $2,200 in subsidies, up from $540 in 2006.

“Over the last four years the state legislature cut half our appropriation,” Norm Arkans, the school spokesman, said by way of explanation.

“Over the last four years the state legislature cut half our appropriation,” Norm Arkans, the school spokesman, said by way of explanation.

This type of student subsidy began at private colleges in the 1970s and spread to public schools in the 1980s, said Joni Finney, of the Institute for Research on Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania.

Campuses supporting the practice say it helps build a more diverse student body and provides a path to the middle class for lower-income students.

But opaque college financing generally keeps this accounting hidden from public view, Ms. Finney said, largely to keep a lid on complaints from parents.

“Institutions don’t want people to know how they are financed because you might get upset,” she said. “We barely accept the idea of redistribution of income at the government level and this is basically what we’re doing in higher education.”

Schools say shrinking state support for higher education has forced them to ask more of students who can afford it. Between 2001 and 2011, state aid to public universities in the U.S. fell 21%, on a per-student, inflation-adjusted basis, according to the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, a national research and advocacy group.

Over that same period, tuition at two- and four-year public colleges rose 45%, when adjusted for inflation, to $4,774, according to the association.

The rising costs—and subsidies—have prompted greater scrutiny and political protest in such states as Texas, North Carolina and Iowa.

“It’s an additional tax, and it’s hidden,” said Fred Eshelman, a member of the Board of Governors at the University of North Carolina, where the cost of set-asides has tripled to $1,724 in 2012 from $535 in 2006, according to university officials. “If folks are paying full boat and supporting others without knowing it, I don’t think that’s right.”

The tuition subsidies triggered heated arguments in Iowa after a state representative criticized the practice. When he learned of it, James Twedt, a 50-year-old father of three in Urbandale, Iowa, sent an email to his state representative calling the system “nuts.”

Mr. Twedt earns about $90,000 as a manager in an insurance office, and his children don’t qualify for federal aid. He estimated the set-aside program would cost his family about $20,000 through four years of college. He expects each of his children will graduate with about $25,000 in student loan debt.

He said he began saving for his children’s college education when they were born: “My father used to say if you want a helping hand look at the end of your arm.”

That view ignores the public subsidies that go to all students at state schools from taxes, endowments and other sources, said Sandy Baum, a senior fellow at the George Washington University Graduate School of Education and Human Development. Even full-pay students shoulder only a fraction of the cost of their education at public colleges, she said.

The help to poorer students by classmates hasn’t closed the education gap. Students from the wealthiest 25% of U.S. households are nearly nine times more likely than students from the poorest 25% to earn a bachelor’s degree by the age of 24.

In the current budget squeeze, there is stepped-up pressure on schools to admit wealthier students, often with merit scholarships as an inducement. The students neither accomplished enough to earn merit scholarships nor poor enough to get need-based aid end up the hardest hit. “If you’re not rich or your kid’s not a rocket scientist, you’re screwed,” Mr. Twedt said.

In California, tuition set-asides are listed as “return to aid” and now make up 28% of tuition, up from 22% in 2005. Last year, the total was $601 million across the University of California system, up from $201 million in 2005.

In Nevada, the set-asides cost full-time students at the University of Nevada Las Vegas $588 a year, up from $60 in 2004. State higher education chancellor Dan Klaich called it a necessity.

“What we have in Nevada is a huge low-income, first-generation population,” Mr. Klaich said, “If you lose this generation, you’re going to end up paying for it on the other end. It costs eight times more to put a person in prison for a year than to educate them at the University of Nevada, Reno.”

Seeking to expand their student body, schools have increased the amount of funds they funnel to poorer students. In the 2011-12 academic year, public and private U.S. universities gave away $33 billion in scholarships, up from $23 billion in 2006-07, adjusted for inflation, according to the College Board.

Enrolling more students at schools charging higher tuition has led to an explosion in student debt, estimated at $1.2 trillion. Per-student borrowing climbed 55% in inflation-adjusted dollars between 2002 and 2012, according to the College Board. Students with debt now owe, on average, nearly $30,000.

“We used to believe that public higher education benefited all residents of a state, not only the people who were attending, because the more highly educated workforce meant more economic growth,” said Ronald Ehrenberg, director of the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute. “But now our society has moved toward the notion that the people who are paying are the ones who will benefit, so they should pay.”

Higher-income public university students in California are taking on debt faster than others. Among students from families earning between $125,000 and $150,000, 39% now graduate with loans, up from 28% in 2005. The average loan amount increased to $19,310 from $13,470.

By comparison, 66% of students from families earning from $25,000 to $50,000 graduated with loans in 2012, down from 68% in 2005. The loan amounts increased to $18,071 from $15,081.

“Tuition increases have contributed to increase in borrowing,” said David Alcocer, interim director of student financial support at the University of California. He called the debate over tuition subsidies “a convenient distraction from the more fundamental issue, which is a sustained disinvestment in public higher education by the state.”

The growing subsidies have driven calls for more disclosure. Recently, the governing body of the University of North Carolina voted to include more specific language about the subsidies on tuition bills.

The Texas legislature passed a mandate in 2009 that public schools publish the rate of set-asides on tuition bills after the student subsidies nearly doubled at the state’s largest university, Texas A&M, in less than a decade.

Some Texas students set up a website calling for the end to the set-asides. Shawn Johnson, one of the organizers, said he didn’t know he had been paying them until his senior year. “At first, I just felt robbed,” he said. When he graduated, he owed $22,000 in student loans.

In Wisconsin, where the legislature sets tuition for state schools, administrators on different campuses asked for more money to offset cuts in state subsidies. In 2009, the state’s flagship school tapped its wealthiest students in “The Madison Initiative for Undergraduates,” which added $1,000 a year to the tuition of in-state undergraduates and $2,250 for out-of-state students.

The surcharge, which came on top of tuition hikes that have averaged almost 7% a year, raises about $40 million a year. About half the money is used for need-based financial aid; the rest goes to faculty and programs. Other public schools around the state have adopted similar initiatives.

When the practice became widely known in Iowa the political backlash was so intense the Board of Regents decided in 2012 to end it. In exchange, they asked the legislature to give schools $40 million to help poorer students pay for school. The money wasn’t appropriated.

“Iowa students and parents don’t feel it’s fair,” Gov. Terry Branstad said. “I agree.”

Iowa schools froze tuition for the first time in three decades, in part because the tuition set-asides were killed. Mr. Branstad said he hoped private fundraising will help fill the gap.

Mr. Twedt said he was happy subsidies ended before his youngest child goes to school.

“I feel like I’m paying not only for mine but for somebody else’s,” he said. “I give my charity elsewhere. I don’t expect to do it at the state university.”